From London Councils. Clearly we need to campaign to preserve London school funding and for an increase in the total amount spent on schools so that children outside London receive fair funding.

Taking this into account as well as the increased cost pressures identified by the National Audit Office, London’s schools will need to make savings of £360 million in the first year of the new national funding formula (2018/19) to balance their books. No school will gain enough funding from the NFF to compensate for increased cost pressures due to factors such as inflation, pensions and national insurance.

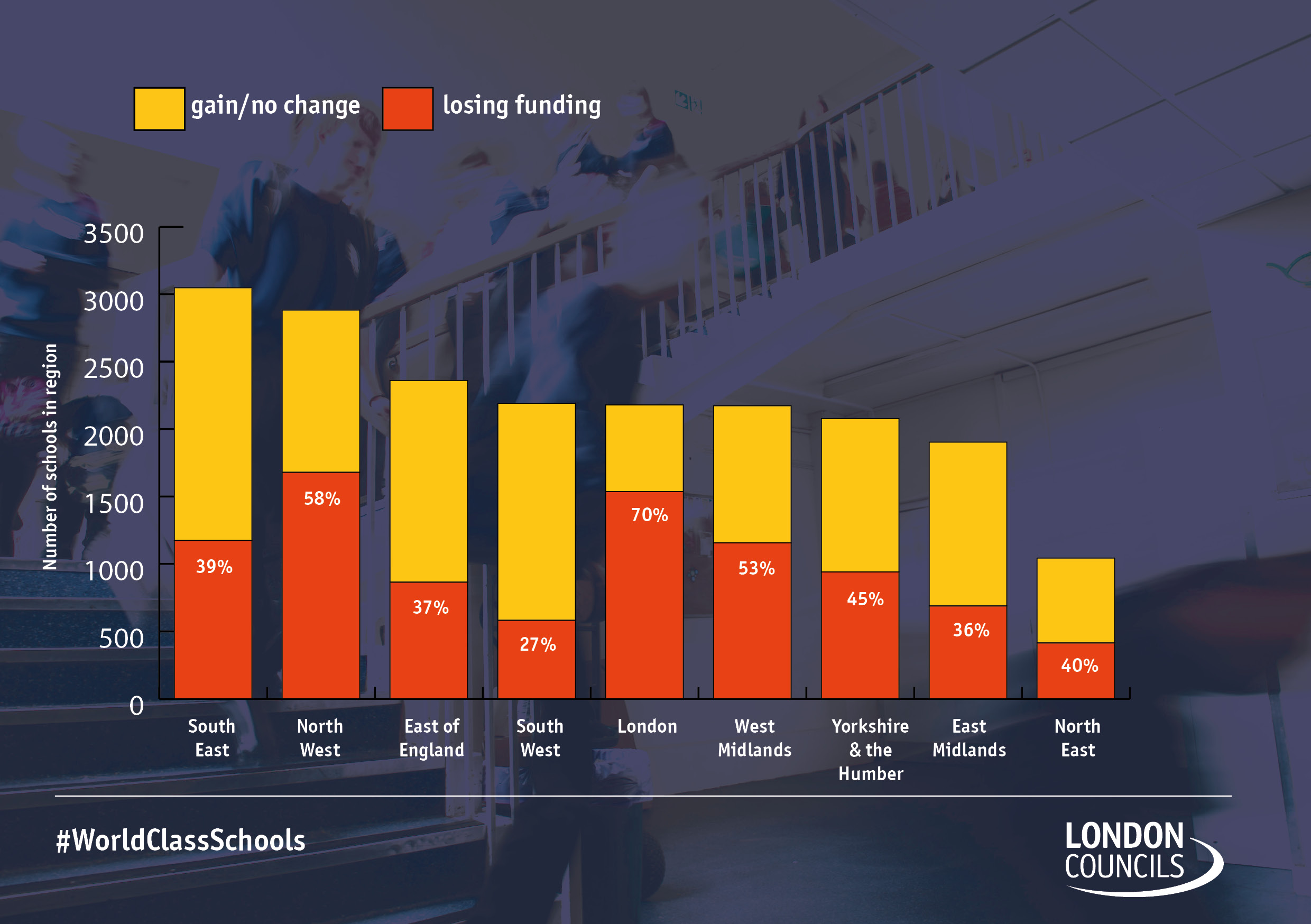

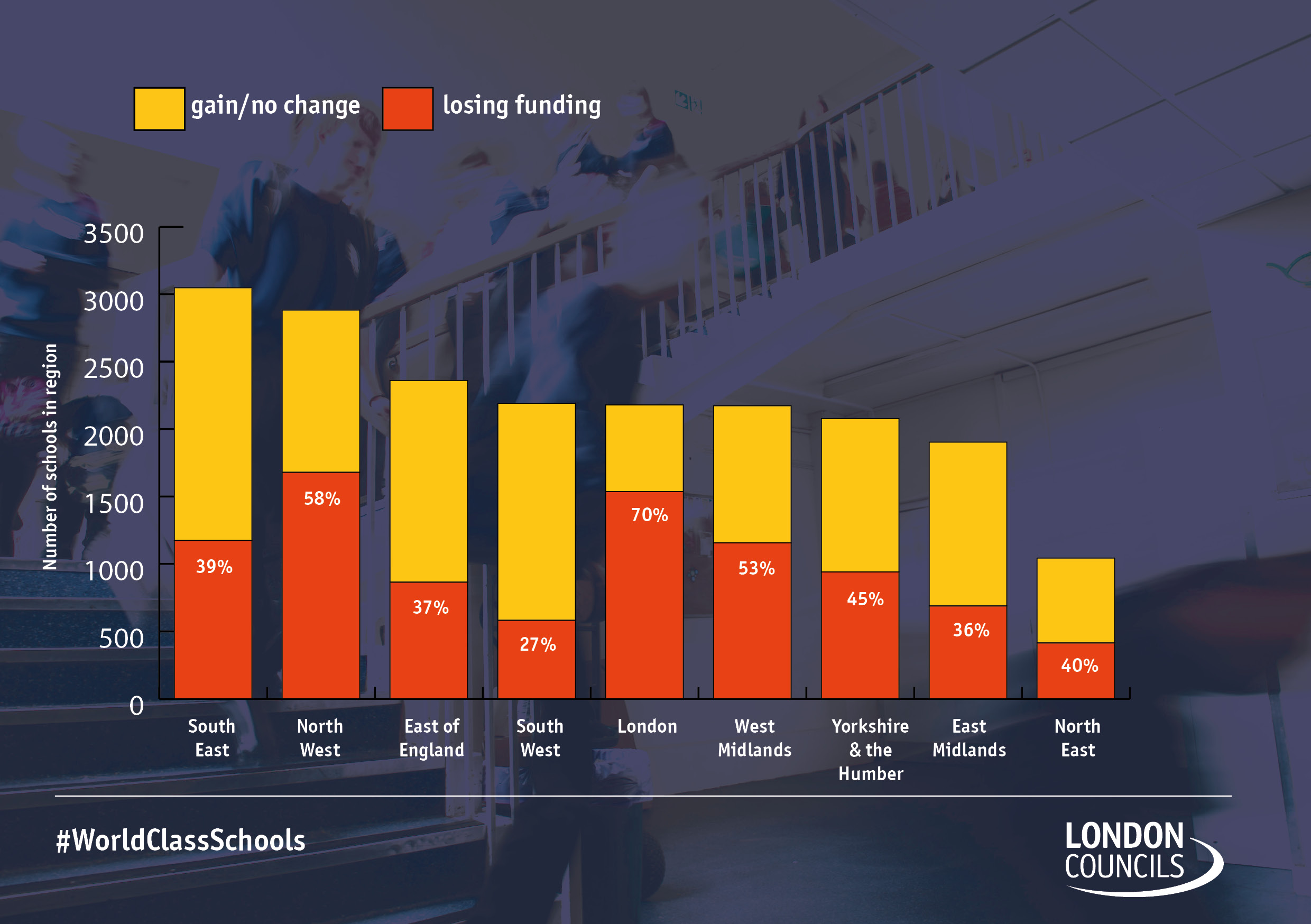

If the government’s proposals are brought into effect, 70 per cent of schools in the capital will face budget cuts, on top of pre-existing funding reductions. London will also see larger reductions in funding than anywhere else in the country.

This comes on top of National Audit Office figures showing that educational standards across the country could plummet as schools in England face an 8 per cent real-terms cut per pupil by 2019/20 thanks to wider cost pressures.

Taking everything into account, London’s schools will need to make savings of £360 million in the first year of the new national funding formula in order to balance their books.

But at a time when UK schools are seen as underperforming by international standards, and when businesses based in London are facing massive uncertainty about recruiting skilled staff, there is an urgent need to invest in schools in London and across the rest of the country.

London Councils' Key Asks:

More on the situation of schools in Brent HERE

The National Funding Formula (NFF)will remove £19 million of funding from London’s schools.

Taking this into account as well as the increased cost pressures identified by the National Audit Office, London’s schools will need to make savings of £360 million in the first year of the new national funding formula (2018/19) to balance their books. No school will gain enough funding from the NFF to compensate for increased cost pressures due to factors such as inflation, pensions and national insurance.

As around 70 per cent of a school’s budget is spent on staff salaries, funding reductions are likely to result in fewer teachers and support staff posts in schools, as well as increased class sizes.

This is significant because top quality teachers who are motivated

and highly skilled are the main reason that children make progress and

achieve good results in their education.

Without the right qualifications and skills, London’s children will

be unable to access jobs and contribute to the national economy. Over

60 per cent of jobs in inner London require a degree and around 45 per

cent of jobs in the rest of the capital require a degree.

Analysis of the NFF shows that:

- 70 per cent of schools (over 1,500) across the capital will face budget cuts.

- The impact is widespread – 802 schools in inner London and 734 schools in outer London stand to lose funding due to the NFF.

- At least one school in every London borough will experience a reduction in funding.

- 19 London boroughs are set to lose funding, with losses ranging from 0.1 per cent to 2.8 per cent.

Combining the impact of the introduction of the NFF and wider

cost pressures, headteachers at London schools will have to make savings

totalling £360 million in the first year of the NFF (2018/19).

The savings required are equivalent to:

- 17,142 teaching assistant posts, on an average salary of £21,000.

- 12,857 qualified teachers, on an average salary of £28,000.

- This amounts to cutting 7.5 teaching assistant posts per school or cutting 5.6 qualified teachers posts per school, given that there are 2,297 mainstream schools in London.

If the government’s proposals are brought into effect, 70 per cent of schools in the capital will face budget cuts, on top of pre-existing funding reductions. London will also see larger reductions in funding than anywhere else in the country.

This comes on top of National Audit Office figures showing that educational standards across the country could plummet as schools in England face an 8 per cent real-terms cut per pupil by 2019/20 thanks to wider cost pressures.

Taking everything into account, London’s schools will need to make savings of £360 million in the first year of the new national funding formula in order to balance their books.

But at a time when UK schools are seen as underperforming by international standards, and when businesses based in London are facing massive uncertainty about recruiting skilled staff, there is an urgent need to invest in schools in London and across the rest of the country.

London Councils' Key Asks:

- That all children receive a great education – every child in the country deserves this.

- That the government finds an additional £335 million for the schools that stand to gain through the National Funding Formula without taking money away from other schools.

- That the government revises the draft National Funding Formula to better reflect London’s needs and to avoid a decrease in educational standards.

Key facts about London Schools

The figure is 94% in Brent

- In London 89 per cent of schools are currently judged to be good or outstanding by Ofsted, the highest percentage of any region in England.

- Last year London’s schools helped pupils to achieve 60.9 per cent five A* to C GCSEs including Maths and English, the highest rate for any region and above the national average of 57.3 per cent.

- London has the highest attaining cohort of pupils on Free School Meals in the country – 48 per cent of young people on FSM in London achieved five good GCSEs as opposed to only 36.8 per cent of the same group nationally.

- Around 50 per cent of headteachers in London are approaching retirement. Schools must act now to ensure teachers in senior leadership roles are ready to become headteachers.

- Living costs are higher in London. One example of this is private sector rents, which are more than twice the national average according to the Valuation Office Agency. Schools are therefore under pressure to ensure salaries reflect this reality.

- Between 2010-2020 the school age population in London is anticipated to grow by almost 25 per cent

- 110,364 new school places will be needed in London between 2016/17 and 2021/22 to meet forecast demand. This consists of 62,934 primary places and 47,430 secondary places.

- At least £1.8 billion will be needed to provide sufficient school places in London between 2016/17 and 2021/2

More on the situation of schools in Brent HERE