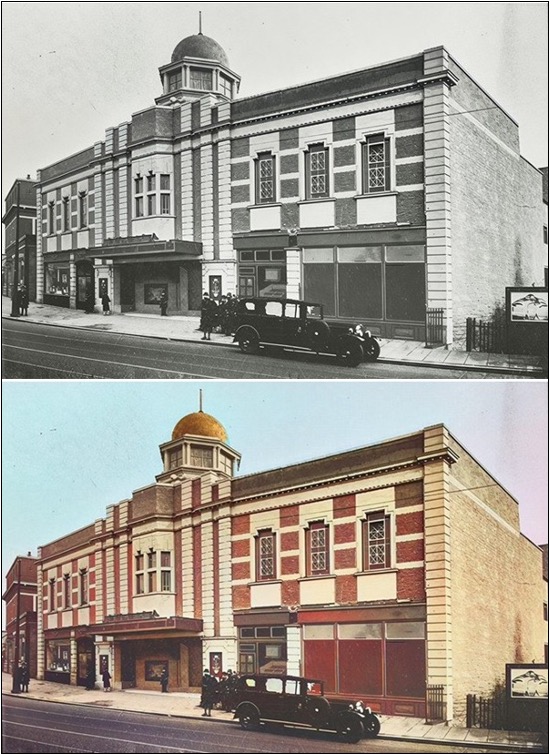

Part 2 of Local History Post by Tony Royden and Philip Grant:

1.The Exterior of the Majestic

Cinema, just before its opening, in original black & white and colourised.

(“Kinematograph Weekly”, 17 January 1929 – original

image courtesy of the British Library)

Welcome back to the second part of the Majestic Cinema’s story. If you

missed Part 1, you can find it HERE. In this article, some of the original black and white photographs have

been colourised, using AI, to help show the splendour of this ‘super cinema’.

By December 1928, the builder’s hoardings had been removed and Wembley’s

new super cinema was in full resplendent view. Passers-by would stop in awe at

the new “majestic” building: The architects, Field and Stewart, had erected a

handsome frontage constructed of Luton grey facing bricks and Atlas white stone

dressings. At the heart of the structure, rising elegantly to the top of the

building, was a gleaming copper dome, held aloft by a drum of Atlas stone

columns, inset with stylish bay windows. Extended over the main entrance was a

striking bronze canopy, shining warmly under carefully crafted lighting. At

sunset, the entire façade could be seen bathed in floodlights. The intricate

frieze, the sweeping cornice and decorative pillars were highlighted by a

subtle, yet dazzling light effect – it was a sight to behold.

On 14 December the “Wembley News” carried a half-page advertisement,

announcing: ‘In a few weeks’ time the Wembley Majestic will be opened, and the

public will be able to visit this veritable Wonder Cinema, where they will be

provided with absolutely the most up-to-date and best that can be offered in

the world of entertainment.’

2.From a full-page advertisement in the “Wembley News”, 11 January 1929.

(Brent Archives – local newspaper

microfilms)

Four weeks later, on the morning of the Majestic’s grand opening, a

full-page advertisement appeared in the Wembley News, which carried the headline

‘A Real Cinema for Wembley at last’. We can only speculate what the owners of

the existing Wembley Hall Cinema, and the Elite Cinema (located in the former

British Empire Exhibition Conference Hall in Raglan Gardens - now Empire Way – which

had only opened in March 1928), thought about that headline! But they would

soon have a chance to find out how popular their new competitor was.

What happened regarding the cinema chain which had plans to open own their

‘super cinema’ directly across the road from the Majestic? We know planning

permission was granted and bricks were delivered onsite to start construction ...

but they were simply too slow. The Majestic’s lightning pace from conception to

completion, in just 12 months, won the race and it’s safe to assume that the

cinema chain must have got cold feet and abandoned their plans. The derelict

land where they had intended to build (at the corner of the High Road and Park

Lane) went on to become high street shops, with a bank on the corner itself.

The Majestic’s opening night, on Friday 11 January 1929, was by

invitation only, but enough invitations had been sent out to fill its 2,000

seats. The guest of honour was Isodore Salmon, the Conservative M.P. for the

Harrow Division of Middlesex (which included Wembley), who was also Managing

Director of his family’s catering business, J. Lyons & Co. He and his wife

sat alongside another leading local figure, Titus Barham, accompanied by his

wife, Florence. Other invitees included all the members of Wembley Urban

District Council and many of the local clergy.

3.Photo of Mrs R.H. Powis from the 18 January 1929 “Wembley News”

supplement. (Brent Archives)

After the playing of the National Anthem, the lights lowered and the

evening’s programme commenced with a showing of a pre-recorded film. Appearing

on screen was Mrs R.H. Powis (wife of the Chairman) arriving by car outside the

Majestic, where she was presented with a key to unlock the ornamental bronze

doors. On entering, the film cut to inside the auditorium and to Mrs Powis on

stage, declaring the Majestic Cinema open. At that moment, the screen went up,

the stage lights came on and there was Mrs Powis in person to finish her

opening address (wearing the same attire that she had worn in the film). This

was met by rapturous applause from the audience who marvelled at this piece of

technical showmanship – and it may have been enjoyed even more than anticipated

as the film had, perhaps by accident, been shown at double speed, so that it

resembled a slapstick comedy!

4.Mr and Mrs

Powis and the stage party at the opening of the Majestic Cinema, 11 January

1929.

(From the “Wembley News” supplement, 18 January

1929, at Brent Archives)

With the audience in the palm of her hand, Mrs Powis spoke

enthusiastically about the immense local support there had been for the

Majestic Cinema project and what an honour it had been for her personally to

have opened it. She invited the audience to absorb the splendour of the

surroundings, expressing that it was a building they could be proud of. She hoped

the residents of Wembley would appreciate all that had been done for them, and

trusted that they too would come and patronise the theatre when the doors

opened to the public.

Mrs Powis then introduced her husband (Chairman of the Majestic Cinema)

who delivered a much longer speech. He started by praising the enterprise of

his ten fellow directors (also present on stage) who had been willing to risk

their money in this local cinema venture. The building, of which they were

immensely proud, had cost around £100,000 (approximately £5.5million in today’s

money), and no expense had been spared in its making (although, by way of

contradiction, he said that he ‘had to be the drag to prevent them from

spending too much money’). Also appearing on stage were the two local

architects, Messrs Field and Stewart, happy to take a bow when introduced, for

they had designed a building which truly did live up to the ‘Majestic’ name. Mr

Powis then praised the builders, W.E. Greenwood and Son, who had worked

tirelessly, and had engaged seventy-five percent of the labour locally. The

beautiful scheme of decoration throughout the auditorium, which engulfed the

audience, was Mr Greenwood’s concept, with the work carried out to his designs.

5.Two views of the Majestic Cinema’s interior designs, one of which has been

colourised.

(From the “Wembley News” supplement, 18 January

1929)

6.Another colourised

view of the cinema’s interior designs.

(“Kinematograph Weekly supplement”, 2 May1929 – original image courtesy of the

British Library)

In an article published in the “Kinematograph Weekly” on 17 January

1929, there was lavish praise for Mr Greenwood’s ‘unique’ and ‘beautiful

decorative scheme’. The décor was described as being ‘upon atmospheric lines’

and ‘in the Italian renaissance style’. It continued by saying: ‘The patron

looks out onto a beautiful Italian garden. The rich colour-scheme employed is

at once restful and pleasing to the eye. The views of mountains, trees and

temples on the side walls are in relief, and their application is remarkable

for the sense of real depth conveyed to the patron. The various effects

achieved by Mr. Greenwood called for much ingenuity and imagination. The whole

of the ceiling is made to represent an Italian sky, and is unbroken by

ventilating grids or lighting fixtures.’ The Majestic was hailed as being 'the

most satisfactory form of the "atmospheric" type of picture theatre

yet erected in England. '

7.Colourised

view of the Majestic’s auditorium, as viewed from the stage.

(“Kinematograph Weekly”, 17 January 1929 – original

image courtesy of the British Library)

Most of the auditorium’s lighting was provided from the front of the

balcony, as described in “The Bioscope”, 12th June 1929: ‘The floodlights

employed were concealed under the auditorium balcony. The front of the balcony

was divided into 16 different sections, each section being glazed with specially

diffusing glass panels.’ A remarkable feature of the lighting was that there

were no notable shadows.

Another innovative design was used for

ventilation: ‘Air is introduced into the building by a series of louvres, which

are practically invisible behind decorative features which harmonise with the

surroundings, and is extracted through thousands of minute holes in the barrel

roof, which are also invisible.’ The painted plasterwork bushes of the Italian

garden theme also hid the grilles through which music from the cinema’s John Compton

Kinestra organ was played.

8.A 1929 advertisement for the John Compton Kinestra organ. (Image from the internet)

As part of the opening night’s entertainment, the audience were treated

to an organ recital, “In a Monastery Garden”, played by Mr Davies on a Kinestra

organ like the one pictured above. There were also performances by a number of

variety acts including; The Six Ninette Girls, The Plaza Boys, Jade Winton and

The Famous Australs – all backed by the wonderful music of the Majestic

orchestra, conducted by J. Samehtini. After a showing of a current newsreel,

the evening concluded with a screening of the 1928 British-made detective film,

“Mademoiselle Parley Voo”. The opening

ceremony was declared a huge success by all who attended.

So what did the Majestic have to offer? From the early days of its conception,

the Chairman and his fellow directors wanted to be able to bring live West End performances

to Wembley (along with the latest film releases) and they were now set to

accommodate the grandest of stage productions. The Majestic was built with a

50-foot-wide fully equipped stage, twelve dressing rooms for the artistes (six

on either side of the stage – female on one side, male on the other), a musical

director's room, a boardroom and an orchestra pit in front of the stage.

9.The original Ground Floor plan for the Majestic Cinema. (Brent Archives – Wembley plans microfilm 3474)

In the original planning application, the floor plans show the main

auditorium was to have 1192 seats, with a further 432 seats located in the

“Grand Tier” (or balcony) making a total of 1624 – but with subsequent

applications, this was increased to near 2000, making it substantially larger

than many West End theatres. The whole of the seating and furnishing had been

carried out by Maples & Co, a long-established and successful company, expert

in cinema work. The seats were comfortable and every seat gave a perfect view

of the stage and screen.

The High Road entrance to the Majestic led to an octagonal lobby that

was known as a “Crush Hall”. This had an imposing dome above it (not to be

confused with the roof dome visible from the outside), which was expertly

painted with light, airy clouds and cleverly illuminated by concealed lights.

The hall included a pay-box, chocolate kiosk and a side-entrance to a 120-seat

café (with the café’s main entrance from the High Road). The hall extended into

a large foyer where two ‘handsome staircases leading to the balcony’ could be

found, along with the entrance into the auditorium.

10.The Majestic

Cinema’s café.

(“Kinematograph Weekly”, 17 January 1929 – image courtesy

of the British Library)

On the first floor, above the café and shops, was the Majestic Ballroom:

Measuring 107 ft. long and 30 ft. wide, it could comfortably accommodate 500

dancers. In an article published in the “Kinematograph Weekly” on 17 January

1929, the ballroom was praised for being ‘one of the finest apartments of its

kind in the provinces’. Its decorative treatment was carried out on classical

lines and its comfortable ‘"Pollodium" cane furniture was

manufactured by Edward Light & Company Ltd. The ballroom was

self-contained, with its own lounge, retiring room and dressing rooms.

11.A colourised

view of the Majestic Cinema’s ballroom.

(“Kinematograph Weekly”, 17 January 1929 – original

image courtesy of the British Library)

As well as having all the amenities of a classic movie theatre, the

Majestic also had a second floor, known as the “Mezzanine Floor”, where a

luxurious lounge could be found – directly under the roof's dome. Natural light

would have permeated from the circle of bay windows beneath the dome and we can

only imagine how spectacular the views must have been (especially as Wembley

was not as built-up an area at that time, and there would still be some open

fields and countryside to observe).

At the end of the opening night’s extravaganza, around

one thousand of the cinema’s guests, who had remained until the entertainment

programme finished at 11pm, were invited to a reception in the ballroom. They were treated to a

banquet of food and drink, and there was

dancing to the music of Mr Samehtini’s cinema

orchestra. An exhibition was also given of “Modern Ballroom Dancing” (as

described in his 1927 book of that name by Victor Silvester, whose father, the Vicar of St John the Evangelist Church at the other

end of the High Road, had been a guest that evening). The celebration of the

Majestic’s first night went on until 1am on the Saturday

morning.

Wembley’s Majestic Cinema had opened, but would it be a success, and why

can’t we see it now in the High Road? To find out the answers, join us next

weekend for the final part of our story!

Tony Royden and Philip Grant.