Philip Grant concludes his fascinating series on a pioneering Indian in Wembley

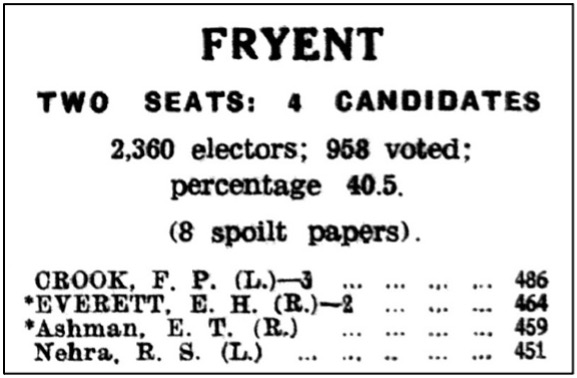

Thank you for joining me for this final part of Ram

Singh Nehra’s story. If you missed Part 2, you can find it here. At the end of that episode, I asked: ‘Did Nehra

stand for election to Parliament?’

Ram Singh Nehra in the 1930s. (Extract from a family photograph, courtesy of

Tyrone Naylor)

I’ve not been able to find out whether Nehra was

chosen as a possible Labour Party candidate for the Commons, but the records of

by-elections from 1936 to 1938 make no mention of him. I wonder whether his

view of British politicians would have changed, if he had been elected, from

that in his report on Parliament’s consideration of the India Bill, in the

autumn of 1935:

‘Politicians are wonderful people. Their power of

speech knows no limits of any kind. They wield such magic through their words

that listeners often wonder if the world is fast approaching its end or the

millennium is just about to dawn. The press is usually an obedient mistress of

the clever politicians. Very few English people know the real facts and

circumstances in their proper prospective.’

There was some happy news for Nehra and his wife in

June 1936, when their third child, Brian, was born (the birth again being

recorded in the Hendon Registration District, which included Wembley). However,

by 1938, Nehra was making the news for the wrong reasons. The headline on a

report about him in January read: “SOLICITOR FINED £100” (which may not seem

much now, but would be about six months’ starting salary for an ordinary local

government employee then).

A disciplinary committee, ‘sitting in public in the

Court Room, Carey-street, London, W.C.’, had found him guilty of breaching the

Solicitors’ Practice Rules. His crime? ‘That he had done or permitted in the

carrying on of his practice acts and things which could reasonably be regarded

as touting or advertising or as calculated to attract business unfairly.’

Solicitors were not allowed to advertise! Was this an advertisement, in his

magazine: ‘If you have any just cause or grievance and have no medium of

expression, write to the Editor of “The Indian”’?

Local newspaper cutting from April 1938. (Image from the internet)

A few months later, another newspaper report

records that ‘Mr R. Nehra, of Chalk Hill Road, Wembley,’ had knocked down an

elderly lady in Dartmouth Road, Willesden, with his car. I don’t know whether

any action was taken against him following this accident, but by that time

Nehra had other activities that he was pursuing.

I referred previously to Nehra writing that his hobbies were ‘building, books, journalism and

social gatherings’. I’ve recently learned that he had “The Shalimar” built for

him and his family on a plot of land he’d bought in Chalkhill Road, but I don’t

know whether he did any other building in the Wembley area. In 1937, however,

he bought a block of land on the coast near Eastbourne. Mr and Mrs Nehra became

directors of Pevensey Beach Buildings Ltd, and their company began developing

an estate of seaside bungalow homes on the East Sussex coast.

A Pevensey Beach Buildings Ltd compliments slip. (Courtesy of Tyrone Naylor)

The Martello Estate was on a block of land between

the main coast road and the beach. Near the seaward end was a Martello Tower,

one of 103 small round stone forts built along the south-east coast of England

in the early 19th century, to defend against a possible invasion by

Napoleon’s French army. The company built two streets of bungalows there,

between 1937 and 1939. At first, Nehra drove down from London a couple of times

a week, to check on progress. Later, the family moved down to a rented home at

Westham Drive, Pevensey Bay.

Nehra found himself in trouble again, and in

December 1938 he was in court, defending his company against a prosecution

brought by Hailsham Rural District Council. Hailsham Petty Sessions (the local

magistrates) heard that the company had connected the drains from its estate to

the local Council’s sewers. However, it had failed to notify the Council that

it was doing so, or to provide plans showing what it proposed to do, so was in

breach of the Public Health Act, 1936!

Headline from “The Sussex Agricultural Express”, 23

December 1938. (Image from the

internet)

By 1939, the Nehra family moved to 3 Grenville Road

(the street probably named after their oldest child) on the Martello Estate. In

July 1939 their fourth child, Ruby, was born, and her birth was registered in

the Hailsham District [although Pevensey Bay is some distance from the inland

town of Hailsham itself, its Rural District stretched down to the coast]. The

household, by this time, appears to have included a nanny, Emily Westgate from

Hastings, and an under-nurse, Maureen Pickett from St Leonards-on-Sea.

Martello Estate bungalows in Grenville Road, Pevensey

Bay. (Image from Google Streetview)

In September 1939, Germany invaded Poland, Britain

declared war on Germany, and the Second World War broke out. The following

January, the Nehra family sailed from England for India, and their nanny, Miss

Westgate, went with them. They travelled First Class, arriving in Bombay

(Mumbai) the following month. Nehra had hoped that he could be reconciled with

his family, who had disowned him when he married a woman who was white, and not

a Hindu. But when he called on them with Myfanwy, they were not even allowed

into the house.

Luckily, Nehra did have friends in India, and he

and his family were offered the use of a wing in a palace, in the Himalayan

“hill station” resort of Mussoorie, for as long as needed. Myfanwy wrote about

this in a letter from Lucknow to her twin sister, Kathleen (“Kit”), in March

1940:-

Opening page of Myfanwy Nehra’s letter to her

sister, 24 March 1940. (Courtesy of

Tyrone Naylor)

The letter said that they would have to travel ‘the

last few miles by rickshaw’. Writing again ten days later, from the Dilaram

Palace in Camel’s Back Road, she told her sister:

‘We are 7000 feet above sea level and

6000 of it all up one mountain. How they made the road I don't know. It's

swerves round and round – the most fearful hairpin bends - just a narrow road

& ravines straight down. I shut my eyes half the time - beautifully green –

trees etc. - Then rice growing, other parts wild. Not a bit flat just climbing

all the time, round and round. As we turned round some bends one could see all

our cavalcade - about 30 coolies with trunks and boxes on their backs…. [and]

five or six men pushing each rickshaw.’

Myfanwy, Ram, Grenville and Sheila, with Palace

servants and coolies. (Courtesy of

Tyrone Naylor)

Despite the idyllic surroundings, Myfanwy reported

that she had not felt well. We’ve seen before that, in 1935, Nehra had referred

to ‘my wife’s serious

illness’. After just a few months in Mussoorie, the family moved to New Delhi,

for better medical facilities, but on 29 September 1940 Myfanwy Nehra died from

breast cancer, in the Lady Irwin Hospital.

His wife’s death, and the collapse of his solicitor

business in London (in the hands of an employee who proved untrustworthy), left

Ram depressed and without an income. Emily the nanny and his teenage son

Grenville rallied round, and for the rest of the war the family ran a

succession of hotels for British soldiers on leave, in various cities including

Gwalior, Old Dehli and Srinigar. As soon as they could, after the Japanese

surrender had brought the war in the east to an end, they returned to England,

only this time sailing Third Class.

By October 1945, Nehra was back in England, and

sold his detached house in Chalkhill Road to clear his debts. He already knew

that the bungalow at 3 Grenville Road had been repossessed by the Halifax

Building Society during the war, but he went down to Pevensey Bay, to sort out

matters there.

Not long after the Nehra’s had left for India, the

beach and the tower at the edge of it, had been declared a prohibited area, and

fenced off with barbed wire. Britain feared that this stretch of coast might be

where a German invasion landed, with good reason. A mile to the east was

Norman’s Bay, where William the Conqueror’s army landed in 1066. The Romans had

built a “Saxon Shore” fort (now Pevensey Castle, with wonderfully intact walls), to protect their

British province from invaders, and the Martello Tower itself was built for

fear of a Napoleonic attack.

Aerial view of the Martello Estate, from the sea. (Image from Google maps)

Nehra had arranged for some friends, Mr and Mrs

Wilson, who’d bought a home in Grenville Road, to look after the furniture from

his bungalow, and other materials and plant belonging to his building company,

which had been stored in the Martello Tower. After the war, some had been sold,

but they could not account for the proceeds, or what had happened to the rest.

This led to the Wilsons being prosecuted, although they were acquitted by the

local magistrates.

Cutting from the “Eastbourne Herald”, 2 November

1946. (Image from the internet)

The newspaper report of the case said that Nehra

lived at 3 Grenville Road, ‘and also at Preston-road Wembley’. The 1948/49

Curley’s Directory shows his address as 121 Preston Road, and I’ve now learned

that this was the Nehra family’s first home in Wembley, when they arrived back

from Kenya. Ram Singh Nehra had bought the recently-built semi-detached house

around 1929, and named it “Mombasa”. It was rented out when they moved

“upmarket” several years later, but it became their home again after the war.

L to R: daughter-in-law Betty, Ram and Emily, their

daughter Julia and her friend Elizabeth, outside 121 Preston Road, early 1960s. (Courtesy of Tyrone Naylor)

This article was about ‘a Wembley Indian in the

1930s’, but Nehra’s story here continued into the 1940s and beyond. In 1947, he

married his children’s former nanny, Emily Louisa Westgate, and they had a

daughter, Julia, in 1949. He went back to work as a solicitor, specialising in

criminal cases at the Old Bailey. He also continued his interest in causes he’d

championed in the 1930s:

Headed notepaper of the Coloured People’s Aid

Society, c.1960. (Courtesy of Tyrone

Naylor)

121 Preston Road was Nehra’s home for the rest of

his life, and he died there, ‘peacefully, after a short illness’, on 29 June

1965. This story began with a garden party at “The Shalimar”, and the home

which Nehra had built for his family in the early 1930s also came to a sad end

at around the same time. 43 Chalkhill Road was one of the many houses which the

new Brent Council compulsorily purchased, in order to build its Chalkhill Estate (1 to 41, numbered from Blackbird Hill, were

spared!). Einstein House now stands on its site.

Chalkhill Road demolition, c.1966, and Einstein House

now. (Brent Archives / Google

Streetview)

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading about Ram Singh

Nehra. His story not only tells us about the 1930s, through the eyes of an

Indian gentleman, but also raises some thought-provoking points which are still

relevant today. If you have any comments, or any further information (perhaps

you knew Julia Nehra at Preston Manor School in the 1960s?), please add them

below.

Philip

Grant*, Wembley History Society, December 2021.

* Although

I’m the one who has written this article (and any errors are mine), it would

not have happened without the initial enquiry from Winston, and some excellent

online research by my Wembley History Society colleagues, Christine and

Malcolm, to help answer it. Further details about the family came from

Myfanwy’s great-nephew, Arthur, and more recently from Ram’s grandson, Tyrone,

and I’m grateful to them both for their contributions. Local history societies

in Hailsham and Pevensey & Westham also kindly answered some queries from

me.