The

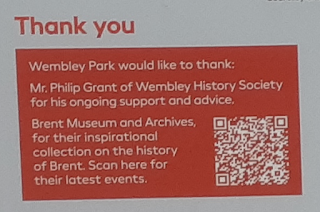

first of a series of guest posts by Wembley History Society member, Philip

Grant.

Some

of you may be thinking of our beautiful local country park as a peaceful place,

where you can go for fresh air and exercise while still “social distancing”.

Others are looking forward to spending some time there, once we are no longer

asked to ‘stay at home’. But have you ever wondered how we came to have this

special open space, or what it was like here 100 or 1,000 years ago? Over the

next few weekends I hope to share its story with you.

1. Looking north across Little Hillcroft Field, towards

Kingsbury.

When

were people first living on what is now the country park? There is evidence

that there was a farm in Roman times near Blackbird Hill. An ancient trackway,

that crossed the River Brent (a Celtic name) by a ford at the bottom of the

hill, continued northwards, just to the west of the modern Fryent Way. You can

follow it as a footpath, branching off on the left about 100 metres north of

the Salmon Street roundabout. The Saxons called this route “Eldestrete” (the old

road), and in the 10th century they used it to mark the boundary

between Harrow parish (where the land was owned by the Archbishops of

Canterbury) and “Kynggesbrig”, now Kingsbury (a place belonging to the King).

2. Harvesting in the 11th century. (From a manuscript, probably in the British Library)

There

was already some farming here by AD1085, when King William I’s Domesday Book

survey was conducted, but much of the land was still woodland. This was enough

to feed 1,000 pigs in the larger Tunworth manor, given by the Conquerer to one

of his knights, Ernulf de Hesdin, with enough woodland for 200 pigs

(‘silva.cc.porc.’) in Chalkhill manor, owned by Westminster Abbey (‘abbé

S.PETRI’) after a gift by King Edward the Confessor.

3. An

extract from the Domesday Book, including the Westminster Abbey land in

"Chingesberie".

On

the Harrow side of Eldestrete, there were some common fields by this time. Here

crops were grown on ploughed strips of land, each a furrow long (hence the old

distance of a furlong, or 220 yards). Some freemen rented fields, where they

could graze sheep or cattle. Hilly ground such as Barn Hill was still wooded,

and villagers who kept pigs could pay “pannage” (one penny per pig) to the lord

of the manor, to let them feed there.

4. Ploughing

in the 11th century. (From a manuscript, probably in the British Library)

Around

1244, about 300 acres of Chalkhill manor were gifted to a religious order, the

Knights of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem. To help provide food for

their priory in Clerkenwell, they established a farm on Church Lane (where the

Co-op now stands) which became known as Freren Farm, after the Norman French

word for “the brothers” (monks and lay brothers) who farmed it. The modern

name, Fryent, comes from that farm.

By

1300, parcels of land in Tunworth manor, had been let out to tenants who cleared

small fields out of the woodland, a process known as “assarting”. Three of

these landholdings to the west side of Salmon Street became farms that lasted

until the mid-twentieth century; Hill Farm (at the top of the rise near the

junction with Mallard Way) and two named after the original farmers, Edwin’s

(later Little Bush Farm) and Richard’s (which became Bush Farm, opposite the

junction with Slough Lane). There were thick hedgerows between the fields and

some woodland remained.

This

increase in farming activity suffered a set-back in the mid-14th

century, when a great plague, carried by rats and called the “Black Death”,

spread across Britain killing over one million people, around 40% of the total

population. The records of Kingsbury’s manor court for 1350 alone show 13

deaths ‘at the time of the pestilence’.

The

country got through that pandemic, just as we will the present one, and the

farming community on what is now our country park recovered. In 1439 much of

Tunworth manor (together with land in Edgware and Willesden) was bought by

Archbishop Chichele of Canterbury. He donated it to a new theological college

he set up in 1442, All Souls in Oxford, which collected rents from the tenant

farmers for the next five hundred years. The Archbishop also had an oak wood in

Harrow cut down, to supply timber for the college roof, which meant some of his

tenants lost their supply of firewood, and acorns for their pigs!

5. The brass

memorial to John Shepard and his wives in Old St Andrew’s Church, Kingsbury.

For

more than 100 years, the tenants at Hill Farm were members of the Shepard

family. We know that they became quite wealthy, from the earliest surviving

memorial in Old Saint Andrew’s Church. This is to John Shepard, who died in

1520, and shows him flanked by his two wives, Anne and Maude, with the eighteen

children he had by them, all depicted wearing fashionable clothes.

When

All Souls College had a map of its lands in Kingsbury drawn in 1597, it showed

Thomas Shepard as the tenant of Hill Farm and many of the nearby fields.

Edmund, John, Richard and William Shepard were among other tenants in

Kingsbury. The Hovenden Map, named after the Warden of the College, is a

remarkable record of the area, giving the names and sizes of the fields, and

who was the tenant of each.

The

map extract below shows the farm and the Hillcroft fields, and you can walk

across this part of Fryent Country Park along a footpath. Treat the short

section of Eldestrete, in the top left corner of the map, as if it were Fryent

Way. At the brow of the hill you will find the footpath, which takes you along

the ridge, with lovely views over the fields, to Salmon Street, near its

junction with Mallard Way.

6. The

Hillcroft fields on the Hovenden Map of 1597. (© The Warden and Fellows of All Souls College, Oxford)

Enjoy

the walk, or at least looking forward to it, and I will take up the story again

next week. If you want to ask any questions, or add some information, please

leave a comment below.

Philip

Grant

LINKS TO OTHER ARTICLES IN THIS SERIES