Guest post by local historian Philip Grant

Wembley Park for sale! (in 1829)

One of the joys of sharing stories you know about local history is when that leads to you finding out things you didn’t know! A series of articles I wrote for “Wembley Matters” during lockdown about the history of Fryent Country Park “uncovered” a Cold War bunker at Gotfords Hill, and an article on the Welsh Harp Reservoir led to the identification of a Victorian steeplechase course at Bush Farm.

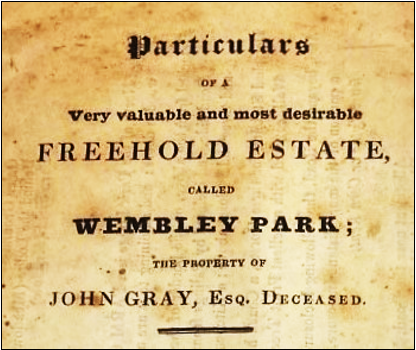

In October, Martin drew my attention to a new comment on The Wembley Park Story, Part 2, written in 2020. A man who was cataloguing a collection, which included the sale particulars for an auction of the Wembley Park estate in 1829, asked whether I would be interested in seeing the document? I contacted him to say “Yes please”! Now I can share with you some of the amazing details of what Wembley Park was like nearly 200 years ago, thanks to the “Particulars” prepared by Mr Christie (James Christie the Younger, who in 1803 had inherited the auction business set up by his father in 1766).

The first part of the detailed Particulars of the Wembley Park estate. (All extracts courtesy of the RICS)

The Lodge at the entrance to the Park is still there, at the corner of Wembley Park Drive, but is “at risk” and awaiting restoration after a fire in 2013. The original drive curved round to the right, before arriving at the Mansion ‘almost re-built within the last fifteen years by the late proprietor, who then expended about £14,000 upon the same.’ John Gray, a wealthy brandy merchant and Freeman of the City of London, who bought the estate in 1804, had spent the equivalent of £1.3m on his new home between 1811 and 1814.

1814 was the year that Jane Austen’s “Mansfield Park” was published, and if you’ve watched film or TV versions of her novels, you’ve probably seen some stylish Regency mansions in those productions. The interior of the mansion in the auction would have been similar. You enter the front door, under a Doric portico, into a ‘Hall paved with Portland-stone, with small diamonds of black marble.’ It probably looked something like this:

The entrance hall of a Georgian or Regency mansion. (Image from the internet)

After describing several rooms off of the hall, ‘a Gentleman’s Study or Library’, a billiard room and ‘a Dressing-Room, and a Water-Closet’ (“all mod cons”, even 200 years ago!), the Particulars move on to describe ‘the Principal Range of Apartments’:

Although the photograph below was taken around 50 years after the auction, the Wembley Park mansion does not appear to have changed much during that time. Nearest the camera on the ground floor is the single-storey Saloon, linked to the bow-fronted Drawing Room, and beyond that the Dining Room, also with a bow window. Above on the first floor are ‘two elegant bow-windowed bed-chambers’. All of ‘this elegant range of apartments looks towards the open scenery of the Park.’

The Wembley Park mansion, c.1880. (Brent Archives – Wembley History Society Collection)

The rooms on the ground and first floors were tall and elegant. On the second floor the ‘Housemaid’s Closets, and one large and one smaller Servants’ bedroom’ had much less headroom. But a mansion this large needed far more servants than that. The rest were housed, along with their places of work, in ‘the Attached Offices’ (while we’re all familiar with what an office is, one old definition of the plural, offices, is ‘the kitchens and outhouses of a mansion.’)

We saw that the Dining Room had a separate entrance door, via a lobby, from the Kitchen in an adjoining building, with ‘steam-pipes ,,, laid from the kitchen to the back of the sideboard’, where the food would be kept warm for serving members of the household and their guests. As well as food there was plenty of drink, kept in an ‘outer and inner Wine-Cellar, with Catacombs’, and ‘an outer and three inner Beer-Cellars’, the beer from their own ‘Brew-house’.

Christmas dinner in a wealthy Regency home. (Image from the internet)

You can read what else the “Offices” include, in the court yard, stable yard and farm yard, which would help to make the estate and its staff largely self-contained community, as long as its owner had sufficient wealth. The farm produced a variety of meat and milk, while vegetables and fruit came from the walled garden, which included ‘a Grapery, Pinery [hothouse for growing pineapples] Green-House, and a Peachery.’ There was also ‘a Large Basin of Water’.

We might call that “basin of water” an artificial pond, which had pipes from it to “the Offices”, for the servants and all their uses. “Squire” John Gray and his family in the mansion were ‘supplied with the finest Spring Water, from a Well, dug at great expense’! And the “basin of water” also had another use. During the winter, whenever it froze over, estate workers would break up the ice and carry it into the nearby woodland, to be stored in ‘a well-constructed large Ice-House’.

The ice house at Harewood House, Yorkshire. (Image from the internet)

Any self-respecting wealthy landowner in the 18th or 19th century would have had an ice house on their estate. It was a building, usually with a brick-lined pit inside, dug into the ground, into which ice was placed during winter. The ice was covered with straw, which kept it frozen for use in the kitchens, to keep food fresh or in making ice cream, in the summer. Wembley Park’s ice house had a thick thatched roof, to help with insulation.

The Particulars go on to describe “The Park”, ‘a fine Demesne of two hundred and seventy-two acres of productive Grass Land’. The stream running through it was described as the River Brent, but was actually the Wealdstone Brook. There were 182 acres on the ‘hither side of the Brent’ and 44 acres called ‘Well Springs, beyond the Brent’. [If you’ve ever wondered how Chalkhill’s Wellsprings Crescent got its name, that’s probably the answer.] There were also 25 acres of timber plantations, an 8-acre horse paddock, two small meadows and an ‘Ozier Ground’. The osier beds, beside the brook, were for growing willow stems, for basket weaving.

Extract from the 1834 Shuttleworth plan of

Wembley Park estate, with coloured details added.

(From a copy of the plan at Brent Archives)

Mr Christie’s Particulars did not include a map, but another attempt to sell Wembley Park, by Mr Shuttleworth in 1834, did include a plan of the estate. On the map above, the roads on the left are now Forty Avenue and Wembley Hill Road (you can just see the cross roads where they meet at East Lane). Near the bottom of the map, the Lodge and ice house are marked. Does the brick-lined pit still exist, perhaps under a garden in Park Chase?

As well as the features within “The Park”, there were 47 acres of fields on the other side of the [Wembley Hill] road, including ‘Public-House Field’, presumably behind the “Green Man”. There were also ‘three Brick-Built Cottages, and two weather-boarded and tiled ditto, in the occupation of sundry Tenants’. Those cottages may still exist, in High Street and by the steep path from there to the “Green Man”.

Last, but not least, was the ‘compact Brick-Built Dwelling’ described above. This was “Wembley Cottage” (some cottage!), which was also known locally as the Dower House, because John Gray’s widow (nearly 30 years his junior) lived there until her death in 1854. It actually survived until about the time of the First World War, renamed “Hillcrest”, at the corner of Wembley Hill Road and Manor Drive. And Manor Drive got its name because the road had been built by developers over the site of the Wembley Park mansion, which was demolished in 1908.

Details of Mr Christie’s auction, from the cover of the Particulars document.

I’ve mentioned that there was another auction in 1834, five years after Mr Christie’s sale. On both occasions the estate failed to sell, and the Gray family continued to live at Wembley Park until after the death of John Gray’s son, the Rev. John Edward Gray, in 1887. The most likely reason for the auctions not being successful is that John Gray’s Executors had set the reserve price too high.

Extract from page 3 of the Particulars, with hand-written figures in the margin.

What was that reserve price? We don’t know, as some of the Christie’s archive records were lost in 1941, when their offices were hit by an incendiary bomb. But there is a clue to the bidding on the copy of the Particulars now in the collection at the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors. From hand-written figures in the margin, it appears that the document’s original owner was at the auction, and noted down the bidding. It opened at £20,000, then went up in stages to £27,000, then more slowly to a final figure of £27,600. That figure in 1829 would be equivalent to around £3.5 million today!

The Wembley Park estate was not sold until 1889, for £32,929 18s 7d (equivalent to around £5m today). But thanks to whoever saved the document in 1829, and the man who donated it to the Auctioneers’ Institute in 1903, we have a detailed picture of what it was like 200 years ago. Because (to borrow from an old advert) Mr Christie made exceedingly good Particulars.

I’ve prepared a full facsimile copy of the Wembley Park auction Particulars, with an introductory note, which should be available in the “Archive copies” section of the Wembley local history page on the Brent Archives website in the near future.

Philip Grant.

9 comments:

I am happy to match the final price plus £1. Any takers?

Hello Paul, top you by £5.00! Best wishes, Bruce

But seriously - another brilliant and informative article by Philip Grant. Thanks You.

Fantastic article Philip, as always!

Thank you, Paul and anonymous (28 November at 08:14).

I was only able to write the article because of the "fantastic" actions of others:

Mr Christie and his staff in 1829, for producing such a detailed "Particulars" document.

The person who had a copy of the document in 1829, went to the auction and made some notes on it, and did not throw it away afterwards.

The unknown people who didn't throw the document away, but passed it on over the next 70+ years.

Mr J.R. Watson, an auctioneer in Esher, Surrey, who had the document in 1903, but rather than keep it for himself, donated it to the Auctioneers' Institute for their archive collection.

Angus, who in October this year was cataloguing that collection, which had been inherited by the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, found my article about the history of Wembley Park online, and got in touch via "Wembley Matters"; and

Fiona at the RICS, who agreed to let me come and see the document, then supplied scans of it, so that I could share its story more widely.

It is people like those that local historians owe so much to!

Does anyone know anything about the Cullen family, the main landowners/ first builders in South Kilburn?

Their stone fronted grand house used to be on Malvern Road demolished overnight early 2000's.

Having read Philip's thanks to all those who "made it possible" I can only repeat our collective THANKS to Philip for writing it and of course for Martin for publishing it!

Hello Phillip, I believe John Gray was my Great Great Great Grandfather. Very interesting piece thank you.

Dear Anonymous (5 September at 07:51),

Thank you for your comment. I apologise for the delay in responding to it, but hope you are still checking to see whether I do.

As John Gray, then his son John Edward Gray, were the "squires" of Wembley for much of the 19th century, I would be interested to know what happened to the family after the sale of the Wembley Park estate in 1889.

I learned a lot more about the Gray family during their time at Wembley Park from a book called "Wembley Park and its Eiffel Tower", written by Martin Easdown and published earlier this year.

I don't know if you are aware of the book, but it contains many Victorian photographs of members of the Gray family, in a section on "The Gray Family at Wembley Park".

If you have not seen the book, but want to find out about it, I suggest that you contact the author / publisher at:

marlinova@yahoo.co.uk

Post a Comment